Health

Kiwi CEO Navigates Chaos of American Healthcare System

After an enjoyable family trip to Disneyland, Brad Porter, the chief executive of Orion Health, faced a healthcare dilemma when his nine-year-old son began struggling to breathe. With a flight back to New Zealand scheduled for later that evening, Porter found himself navigating the complexities of the American healthcare system, an experience that starkly contrasted with the more straightforward approach he is accustomed to in his home country.

Encountering Barriers in Care

Porter’s first stop was a local pharmacy in California, where he expected to receive competent assistance. In New Zealand, pharmacists are often able to address minor health concerns effectively. However, in California, he was handed a box of Tylenol (known as Pamol in New Zealand) and told, “we can’t really advise on that,” due to liability concerns. This left Porter puzzled, as a qualified clinician could not assist his son due to systemic limitations.

The search for appropriate care continued at an urgent care facility, where he was informed that they do not treat pediatric patients, even in cases of significant distress. Fortunately, healthcare facilities in the U.S. are numerous but often lack integration. Spotting a children’s medical group across the parking lot, he managed to secure an appointment, despite the usual requirement for registered, insured patients.

Frustrations with Disconnected Systems

Upon entering the clinic, Porter encountered an iPad intake form filled with extensive fields, disclaimers, and consents. Although the use of an iPad suggested modernity, the physician assistant took notes on paper, as their electronic medical record (EMR) system allowed only one user at a time. The experience was marked by redundancy, as three different clinicians asked the same questions, further delaying the care his son urgently needed.

“So, if we had one of those, I wouldn’t need to ask you all this again?”

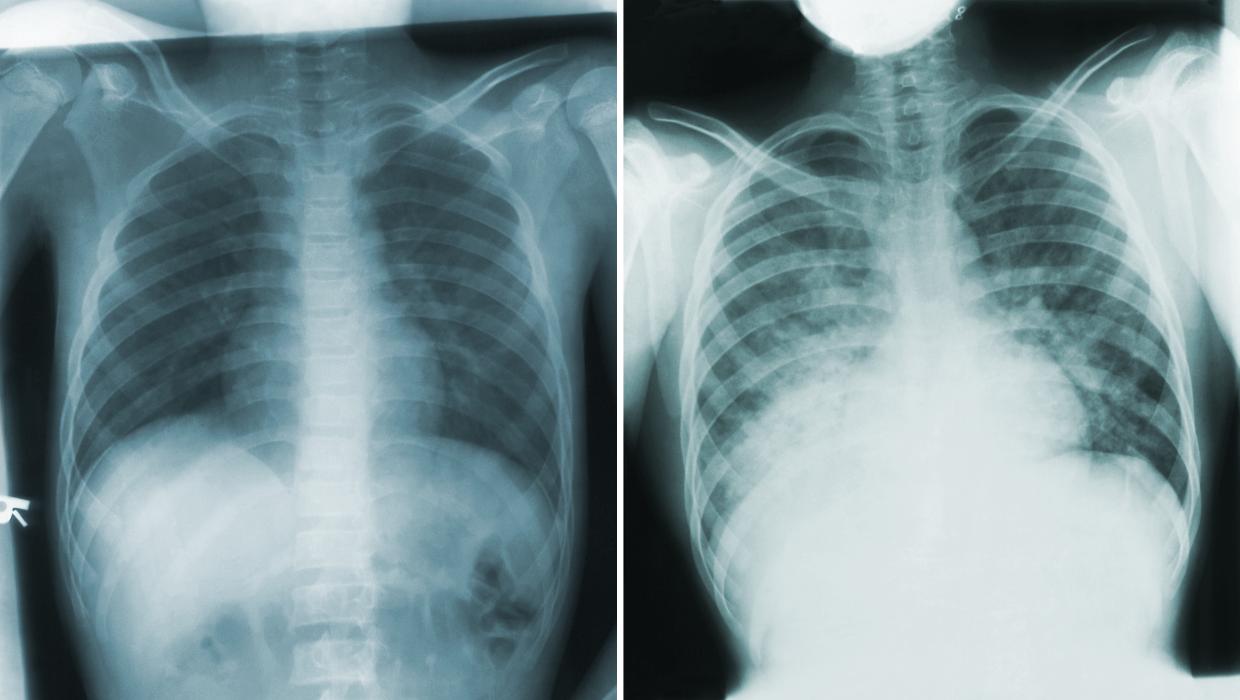

This remark from one of the physicians struck a chord with Porter, highlighting the inefficiencies prevalent in healthcare systems where information is not shared effectively. After a thorough examination, his son was diagnosed with post-viral asthma. The prescribed medications included albuterol, which is referred to as salbutamol in New Zealand. Porter’s familiarity with healthcare terminology helped him navigate this confusion, but it illustrated the dialects within healthcare systems—different terminologies and data formats that create barriers.

Porter noted that standards like the International Patient Summary (IPS) could bridge these gaps, offering a universal format for health data. If such a system were in place between the U.S. and New Zealand, crucial information about his son’s condition could have been transferred seamlessly, eliminating the need for repetitive questioning and potential misunderstandings.

Payment Challenges and Lessons for New Zealand

Despite the impressive care his son received, Porter faced another challenge at the billing desk. He encountered an itemized bill and realized that negotiation could be part of the payment process—a concept foreign to him as a New Zealander. This experience underscored the paradox of American healthcare: innovative practices are often hindered by outdated workflows and a focus on profit over patient care.

Reflecting on his experience, Porter recognized that while New Zealand prides itself on being smaller, simpler, and fairer than the U.S., it too struggles with fragmented healthcare systems. Patients frequently arrive at hospitals without accessible histories, and healthcare providers operate with incomplete information.

Porter’s brief experience in the U.S. served as a reminder that while the chaos of American healthcare is visible, New Zealand’s challenges may be hidden but equally problematic. He argues that complacency in healthcare is dangerous and that a comprehensive system connecting all aspects of patient care is urgently needed in New Zealand.

To improve the system, Porter advocates for the introduction of a single longitudinal shared care record that follows patients from birth to retirement. This would facilitate seamless communication between pharmacists, general practitioners, and hospitals, ensuring that healthcare professionals can provide optimal care without unnecessary delays.

Until New Zealand achieves true system integration, it risks missing out on the benefits of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence. AI could significantly reduce friction in healthcare emergencies by translating terminology, summarizing patient histories, and identifying risks before they escalate.

Porter concluded that although his son recovered and they made it home safely, his experience highlighted the fragility of even the most advanced healthcare systems. New Zealand has the opportunity to learn from these insights to create a more connected, preventative, and patient-centered healthcare model.

-

World4 months ago

World4 months agoTest Your Knowledge: Take the Herald’s Afternoon Quiz Today

-

Sports4 months ago

Sports4 months agoPM Faces Backlash from Fans During Netball Trophy Ceremony

-

Lifestyle4 months ago

Lifestyle4 months agoDunedin Designers Win Top Award at Hokonui Fashion Event

-

Entertainment4 months ago

Entertainment4 months agoExperience the Excitement of ‘Chief of War’ in Oʻahu

-

Sports4 months ago

Sports4 months agoLiam Lawson Launches New Era for Racing Bulls with Strong Start

-

World5 months ago

World5 months agoCoalition Forms to Preserve Māori Wards in Hawke’s Bay

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoWalking Faster Offers Major Health Benefits for Older Adults

-

Lifestyle4 months ago

Lifestyle4 months agoDisney Fan Reveals Dress Code Tips for Park Visitors

-

Politics4 months ago

Politics4 months agoScots Rally with Humor and Music to Protest Trump’s Visit

-

Top Stories5 months ago

Top Stories5 months agoUK and India Finalize Trade Deal to Boost Economic Ties

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoRadio Host Jay-Jay Feeney’s Partner Secures Visa to Stay in NZ

-

World5 months ago

World5 months agoHuntly Begins Water Pipe Flushing to Resolve Brown Water Issue